Note: The functionality discussed in this post is not yet implemented in LZ Desktop.

Because pages on the Static Web (Web 1.1) are self-sufficient and don’t rely on a live connection to the server, they can have a life of their own once downloaded. This will lead to a practice I call republishing. Imagine that anybody can take a page from your website and publish it on their website. Wait, what?!

It may sound crazy at first, but let me explain.

Why would people publish someone else’s content?

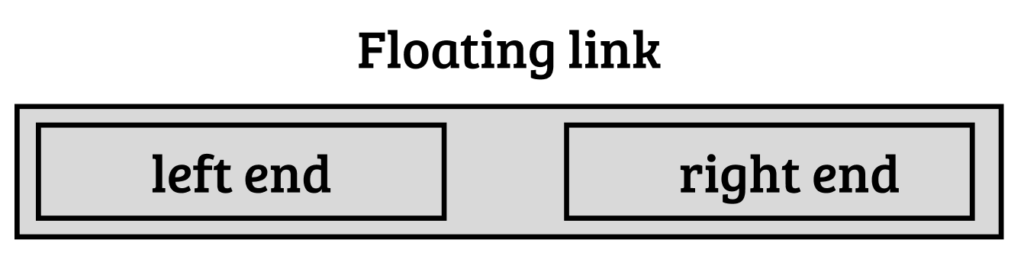

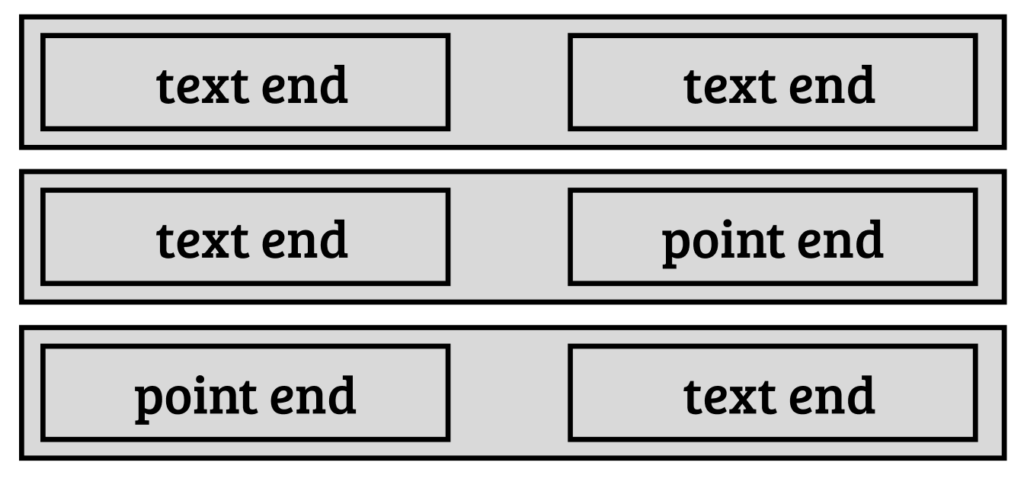

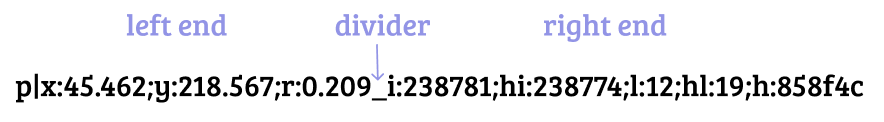

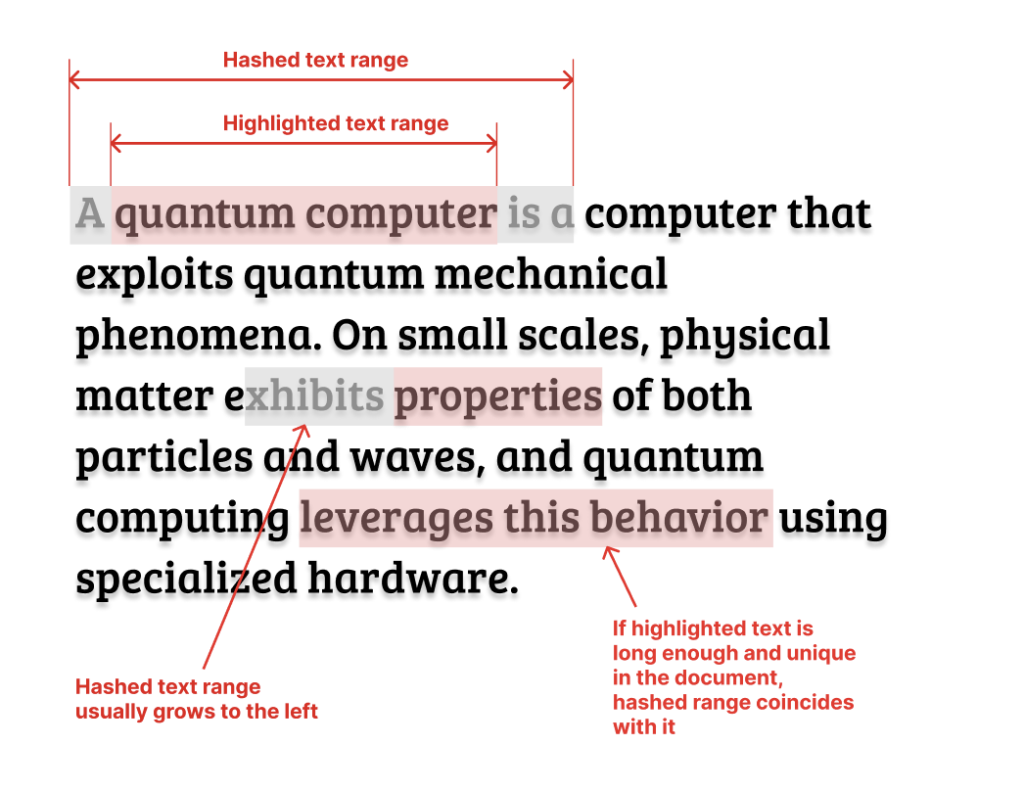

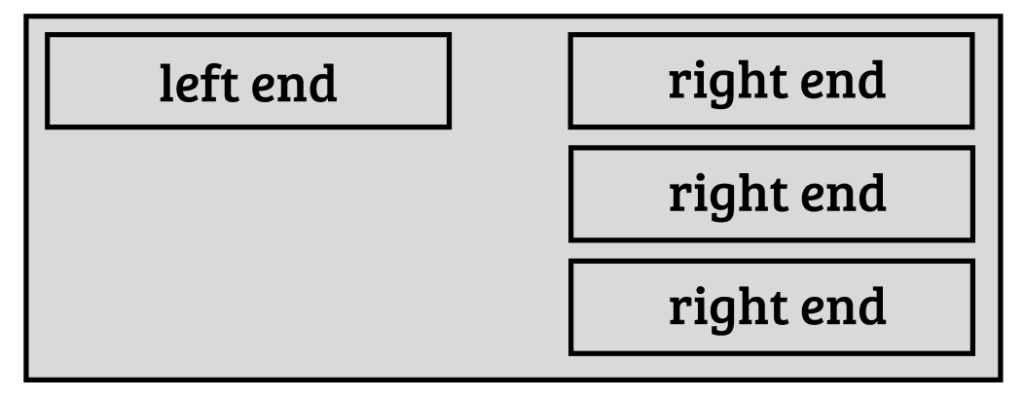

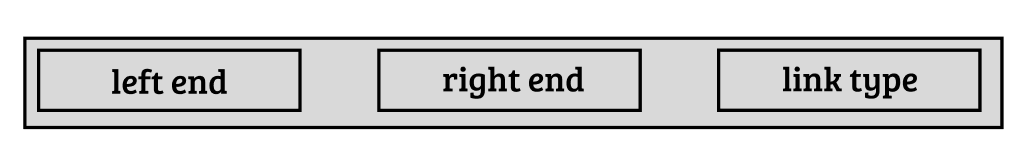

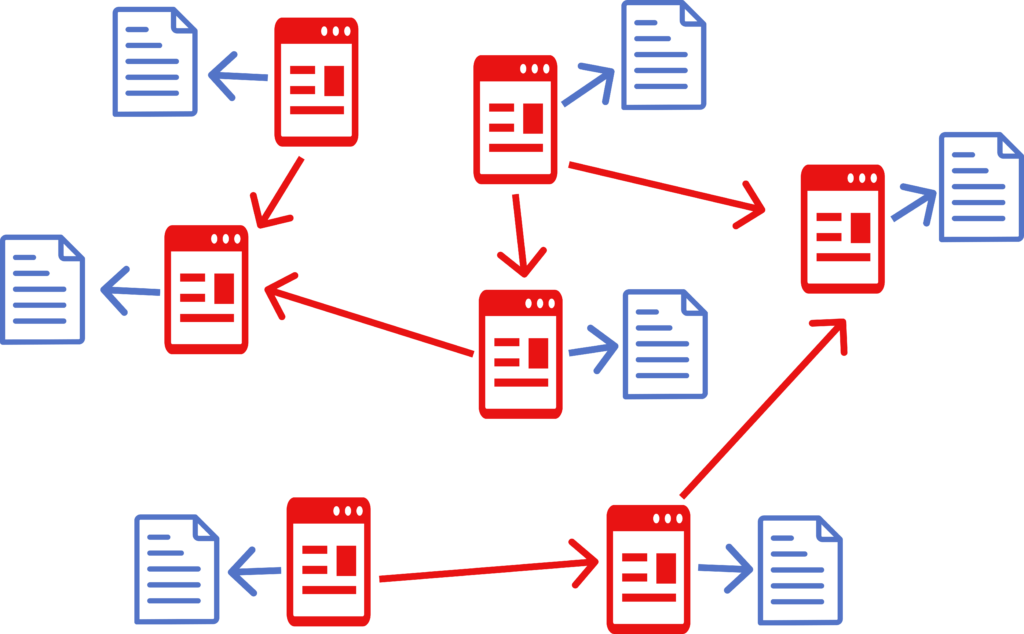

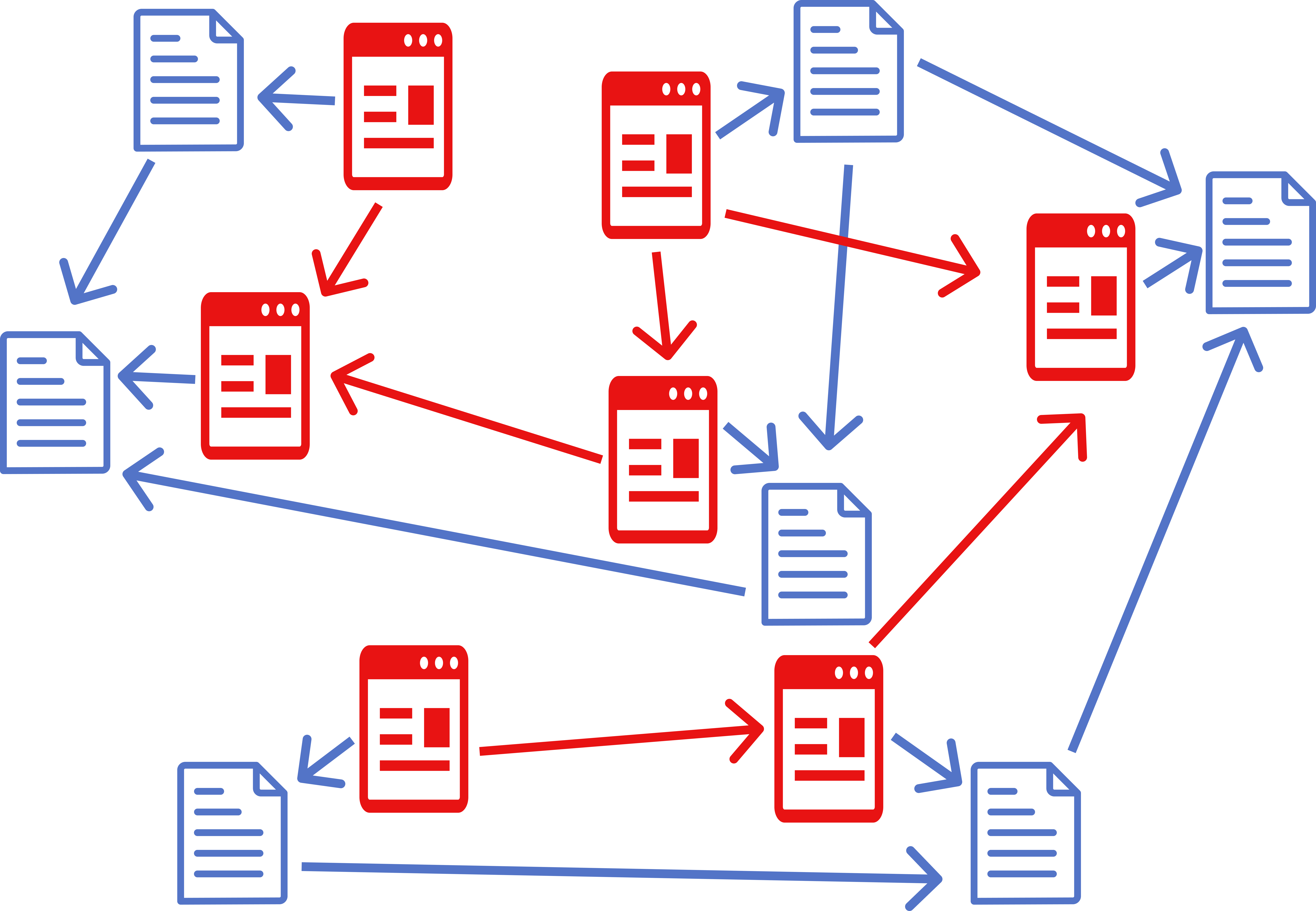

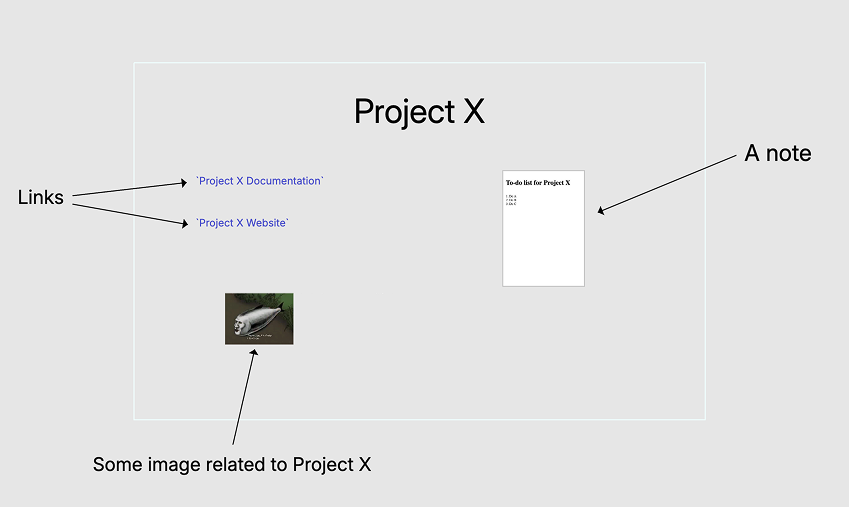

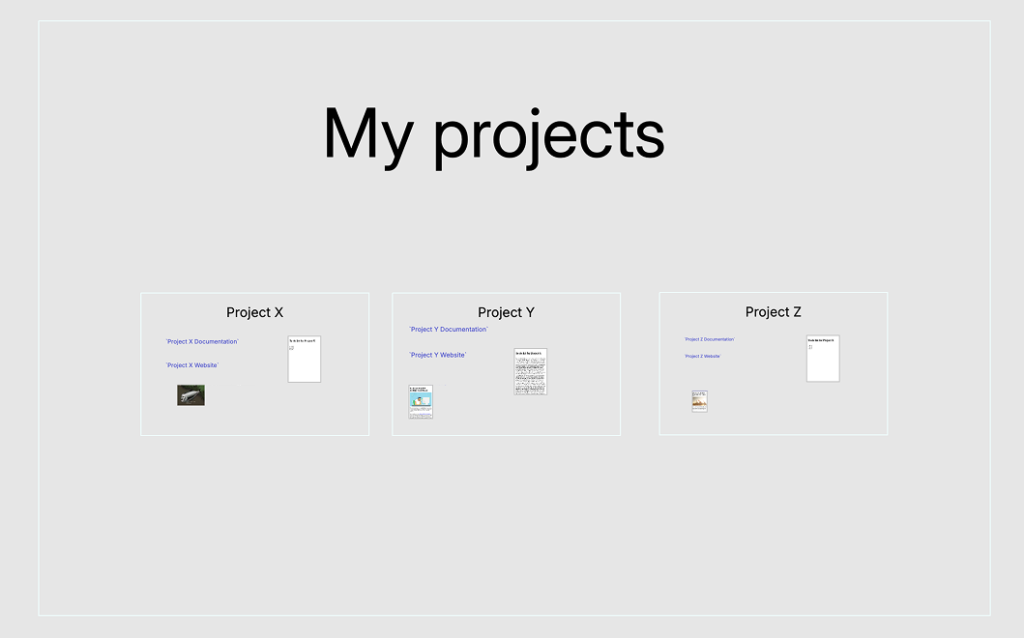

Let’s say you want to publish a commentary on someone’s article. You can create an HDOC, write your commentary, then create a connection to the article in question and create floating links between the two pages. Then you publish HDOC on your website. When someone downloads it, they will see that your document references another document, download that document as well, and then they will be able to see visible connections (floating links) that you created.

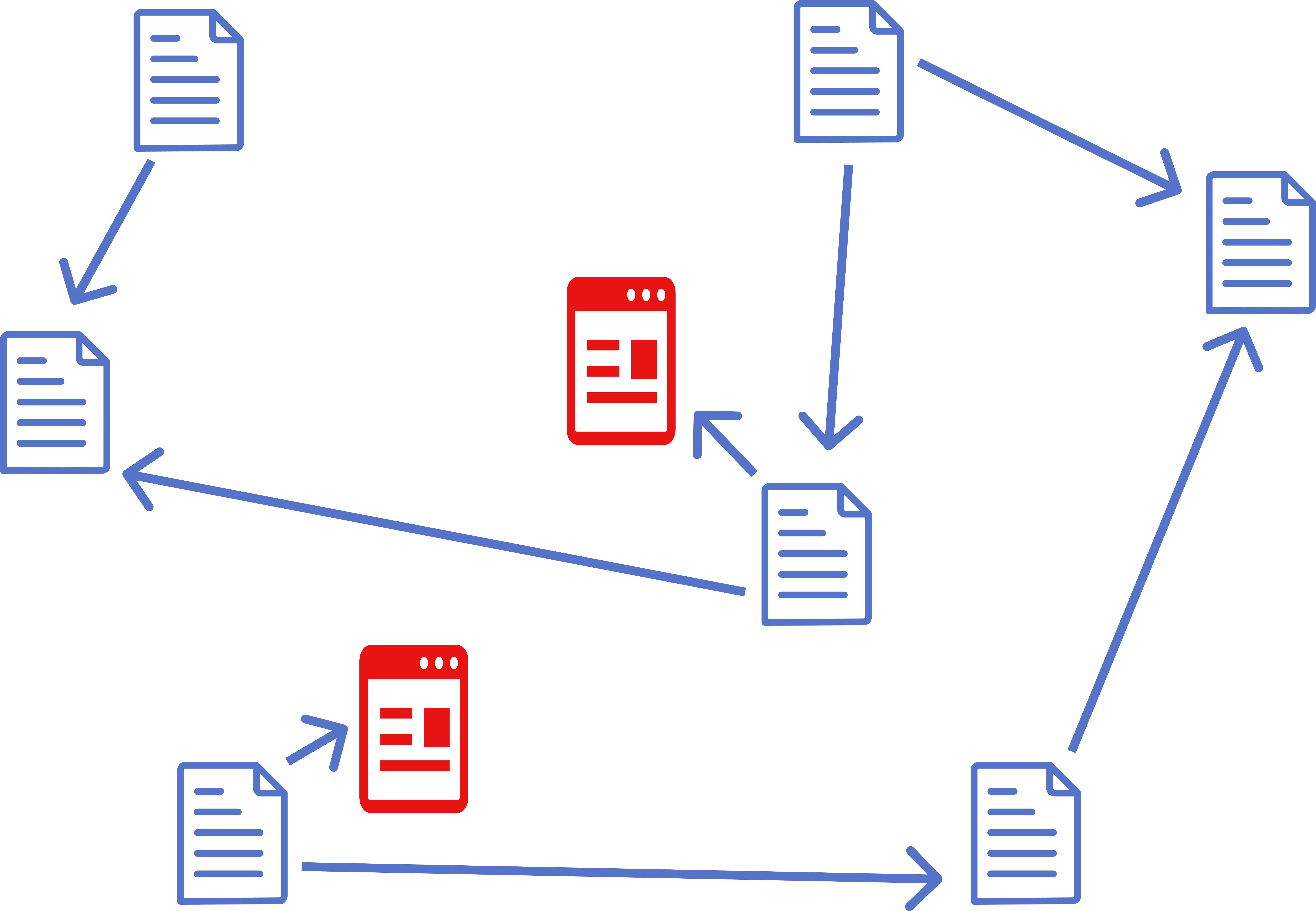

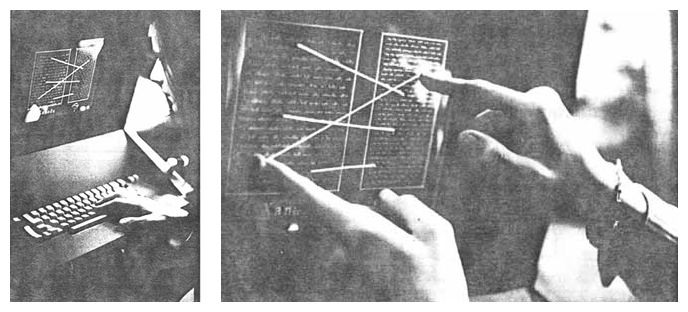

Here is an example of floating links between documents:

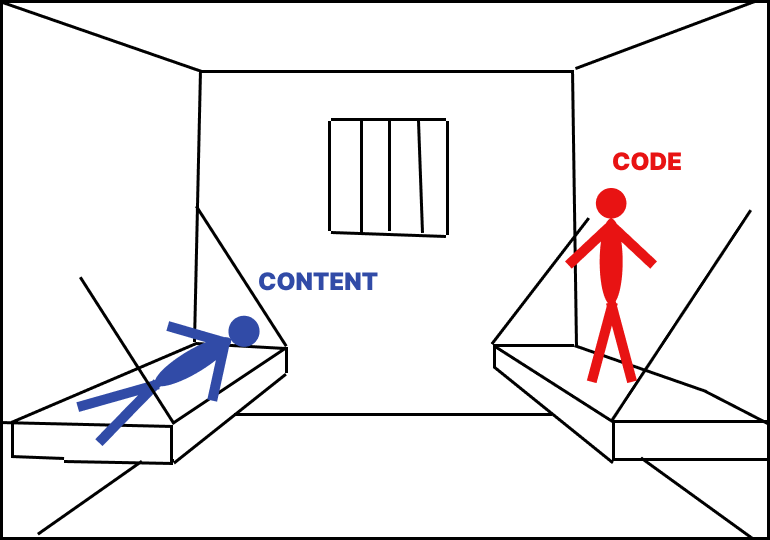

The Problem: Content Instability

All well and good, but what if the author of the article changes something in the article. It may break your floating links. There is a self healing mechanism that can fix broken links, but it doesn’t work in 100% of cases. Or, what if they completely delete their page? All your work writing commentary and adding links would go to waste. You need some way of stabilising the content of their article.

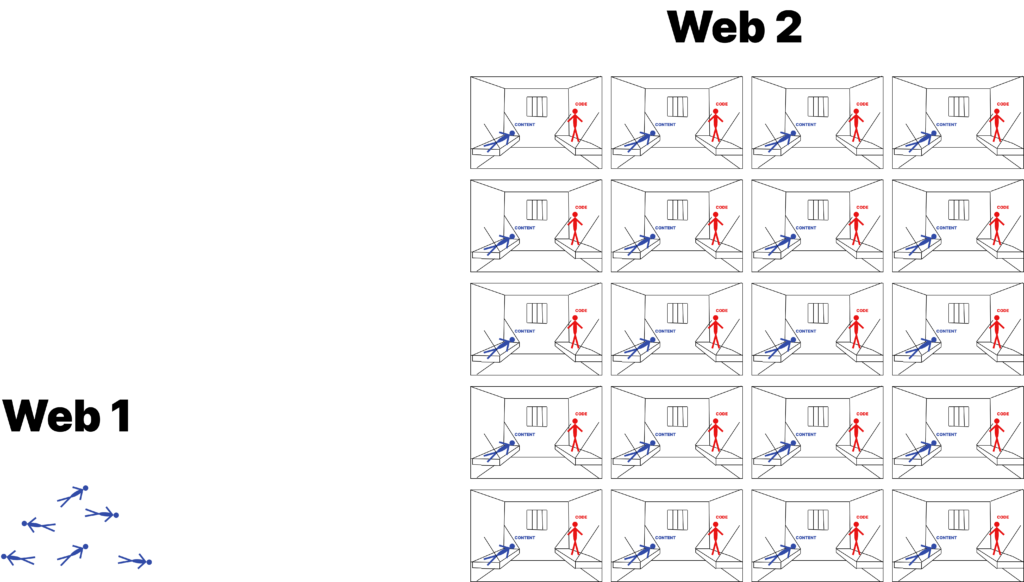

In a centralised system like Ted Nelson’s Xanadu this problem is solved by simply saving every version of every document and never deleting anything. But in a decentralised system like the World Wide Web you don’t have a guarantee that a document on the other end of a link will not change or will even exist in the future.

The Solution: Republishing

The best way to ensure stability in a decentralized system is to host a copy of the article on your own site and connect your commentary to that copy rather than the original.

Is this even legal?

I believe republishing can become an accepted and expected practice, just like linking to webpages is today.

By the way, linking wasn’t always a settled issue. In the early days of the Web some people seriously debated whether it was legal to link to someone else’s page without permission.

Why would that be a problem? Imagine I have a popular website, and you run an obscure one. If you link to my site, your site becomes more useful, possibly gaining popularity. Do you now owe me something for benefiting from my content?

Or what if I publish a private webpage meant only for friends? If you link to it from your popular website, you bring unwanted attention. Should you have asked first?

Today, the consensus is that if you publish content on the Web, you should expect others to link to it. If you want privacy, use authentication. And maybe, you should even be thankful that somebody links to your content, because that brings you more traffic.

Why should you be OK with republishing?

The key is how republishing is done and what the republisher gains from it.

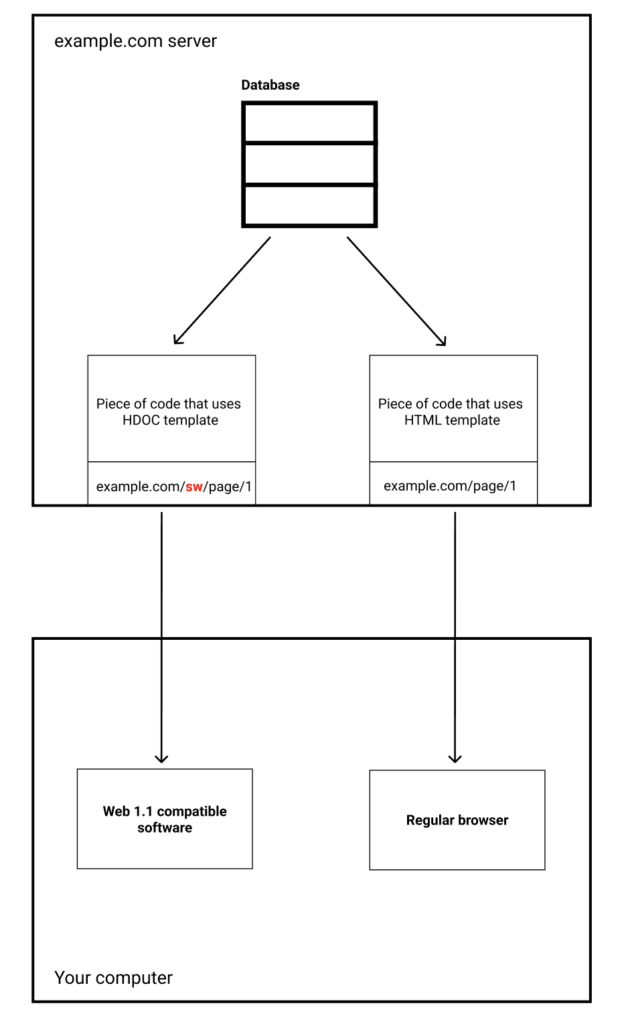

When republishing someone’s page, you must not alter its content. In an HDOC, sections like <metadata>, <header>, <content>, <panels>, and <connections> remain intact. However, a <copy-info> section is added, containing the original page’s URL.

Client software (browsers and storage apps like LZ Desktop) will clearly indicate that the page is a copy, displaying the original URL as its primary address. The page will look as though it was fetched from the original site, while making it obvious that it’s a copy. Users will be able to view detailed information and see its true source.

Search Engines and Republishing

Currently, search engines don’t index HDOCs, CDOCs, or SDOCs, but once they do, they’ll be able to distinguish between native content of a website and republished copies. That means republished pages won’t impact the search ranking of the host site.

More importantly, republishers gain nothing from copying content other than stabilizing it for their floating links. Copying content is simply a technical detail of maintaining floating links, not theft. And just like with linking, you might even be grateful that others are preserving your content for free.

Finding webpages that no longer exist

Search engines could track every republished copy of an original webpage they find, ensuring that if that page disappears, users can still access reliable backups. However, this creates a risk: spammers might try to generate fake copies of recently vanished pages. To counter this, search engines may record multiple versions of each page, storing them as timestamped hashes. This way, when a page is lost, the search engine can analyze a network of its copies, identifying the most recent authentic version. If a spammer attempts to pass off a fake page, hash mismatches will expose the deception.

A Backup System for the Web

Republishing can serve as a redundancy mechanism, solving the problem of broken links.

Random websites will help to preserve only some pages by republishing them.

But in the future, there may exist services similar to the Web Archive that could store vast collections of static pages. These could be non-profits, commercial entities charging for access, or services that you pay to host backups of your content. Different business models could emerge.

Such services could do more than passively store backups. Imagine your browser encountering a broken link. Instead of displaying a “404 Not Found” error, it could automatically request a copy from a backup service and seamlessly load the missing page. The page would be marked as a copy but still deliver the content the user was seeking.

The Interplanetary Web

Now, let’s take this a step further. Imagine a future where humans colonize Solar System. If we don’t do anything about our Web before that happens, there will be a separate Web on each planet, because of time delays in communication between planets.

Many regular web pages are too dependent on live server connections. To have such pages available on Mars, for example, you’d have to have a copy of your entire web server there.

Some popular websites like Wikipedia will probably be hosted this way on multiple planets. But most website owners won’t bother to host a copy of their websites on another planet.

And so, the Web on Mars will be mostly separate and different from the Web on Earth.

However, if we turn our Web into a web of static documents, time delays won’t be a problem. We’ll be able to use republishing mechanisms discussed above to have a copy of the entire Web in many places across the Solar System.

Sure, some things that you have to run in containers, won’t work across large distances. For example, people from Earth and Mars won’t be able to play real time online games together. But that’s expected, and nothing can be done about it.

The problem is that currently our entire Web is made of containers. And this needs to change. Bringing the Web to other planets is yet another reason to start the transformation of the Web.

Republishing License

When I’m ready to implement this functionality, I plan to publish a license or a declaration of principles to clarify the expectations around republishing.

In my view, Web 1.1 is fundamentally about sharing. Readers should be able to download, cache, and even republish content by default.

However, there will also be an option to opt out on a case-by-case basis, ensuring flexibility for content creators who prefer to restrict republishing.

Disclaimer

Of course, none of this is legal advice. I’m not saying you can republish content today without consequences. If you think you could get in trouble for doing so, don’t do it. What I am saying is that republishing could one day become as normal as linking, helping to create a more stable, and scalable Web.