Lately, I’ve been thinking about the Static Web (Web 1.1) and why it allows us to have visible connections, while the current Web (Web 2.0) doesn’t. And I realized that in my very first post — Web’s Biggest Problem. Introduction to Web 1.1 — I completely misdiagnosed the issue.

My Initial Misdiagnosis

I made it sound like the problem is that all content on the Web is locked up in different containers. But that’s not really the issue if what you want is visible connections between web pages.

Yes, the code in the “jail cell” can’t make requests to arbitrary servers. Because of that, you can’t just grab a page from another website, place it next to your own, and show visible connections between the two texts.

The example I had in mind was this prototype:

Moe Juste Origins demo

They were able to show multiple pages side by side with visible connections between them because all those pages were loaded from the same website. If they had tried to load a page from another website, it wouldn’t have worked.

Why That Approach Wouldn’t Work

But even if it were possible to load pages from different websites, what kind of solution is that? To connect texts on two arbitrary pages you’d have to go through some special site that makes it happen? That’s a strange workaround if your goal is to bring visible connections to the Web.

This is why browser cross-domain restrictions aren’t the real problem.

The Role of Browsers

The functionality of visible connections should be built into client apps like browsers, not individual websites.

So the real question is: can browsers present two regular HTML pages side by side and show visible connections between them?

The answer is… yes. Technically, it’s possible.

Yes, web pages run in separate containers, but the main process and those containers can exchange messages. The main process can also inject JavaScript into pages. At least if you are going to develop your browser using Electron, these capabilities are available.

The solution would be complex, with a bunch of moving parts to coordinate. But the bottom line is: it’s possible for browsers to display visible connections between normal pages.

Why Browsers Don’t Do It

Imagine two web pages side by side, each taking half the screen. In many cases, this arrangement would be awkward:

- Pages have headers, footers, menus, and ads that eat up space.

- Some layouts force horizontal scrolling just to see where the connection line goes.

- Pages with active code may change unpredictably as you read.

So, while it would work for some pages, for many it would look clumsy. And on constantly changing pages, it wouldn’t work at all.

Too Much Freedom Inside the “Jail Cell”

Here’s the surprising twist: the Web’s biggest problem isn’t that content is locked inside “jail cells” — it’s that inside those jail cells, content has too much freedom.

There is no standardized layout for a web page. And the presence of code makes content unpredictable.

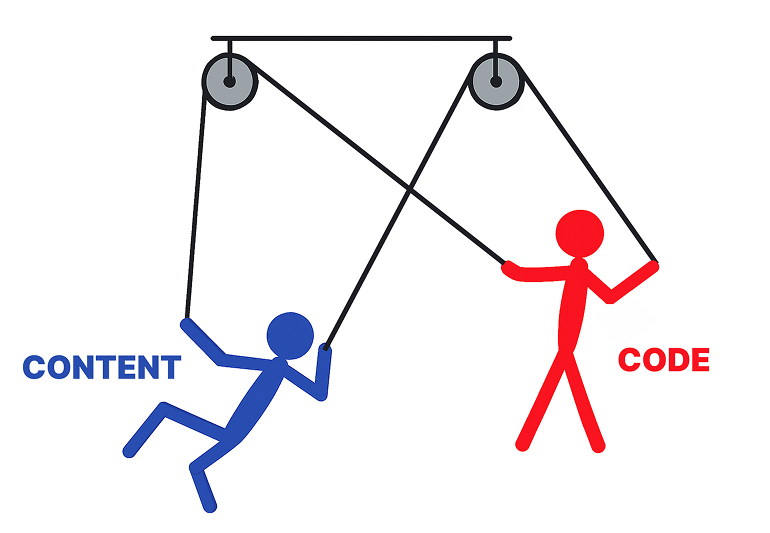

Think of the content and code as two guys locked in a cell together like on the image above. But imagine them dancing together kind of like in the movie Swiss Army Man the main character danced with a corpse using ropes to move the corpse like a puppet.

Remember, the content on its own is paralyzed but the code can make it change unpredictably.

And even without code, web page layouts are unpredictable. Some are simply too strange to reliably support visible connections.

The Real Issue

The challenge I’m trying to solve is how to bring visible connections to the Web. The main reasons it hasn’t happened yet are:

- CSS makes visible connections awkward.

- JavaScript makes content unpredictable.

Yes, because of the code the content is locked up in containers — but that’s not the real problem. The real problem is the lack of a standardized web page.

Why Standardization Matters

Currently, what’s standardized on the Web are the languages: HTML (markup), CSS (styling), and JavaScript (scripting). The idea is that the same code produces the same result in different browsers. But the actual look and structure of the page are entirely up to the author.

Inside your page, you have total freedom.

HDOC, on the other hand, removes that freedom. It enforces a standard layout: one column of text, plus standardized navigation panels that you fill with content but don’t style. No scripts are allowed.

This makes HDOC predictable. And because of that predictability, visible connections will almost always work and look good.

Conclusion

The biggest problem of the Web is not containers, not cross-domain restrictions — but the lack of a standardized page structure.

Without it, visible connections remain unreliable. With it, they could finally become possible.