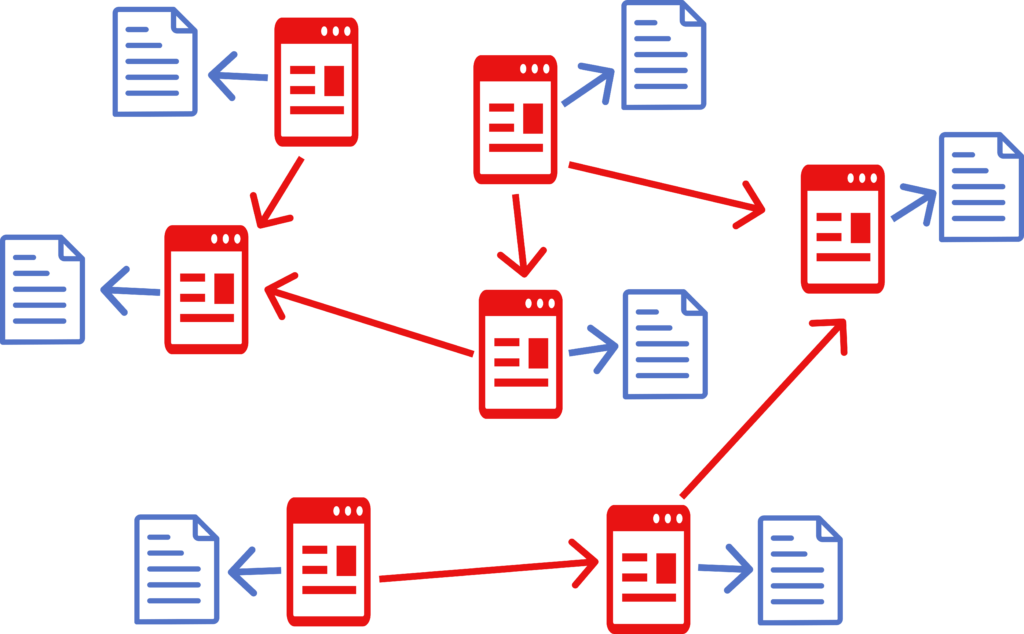

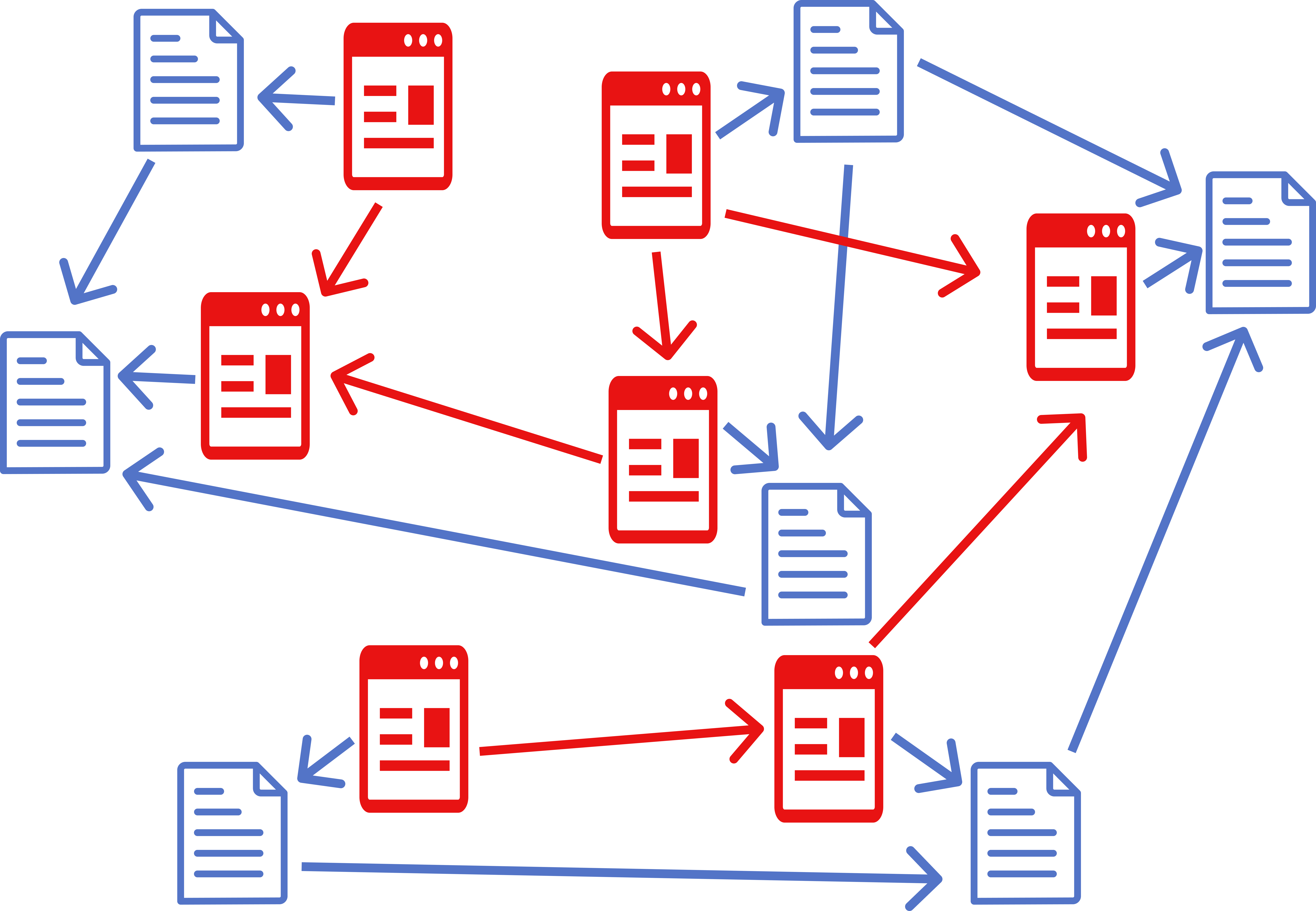

HDOC, CDOC and SDOC may all have <connections> section. It contains a list of documents the current document wants to connect to. Each connection may have a set of floating links.

Child Element: <doc> (multiple)

Contains information about a document.

Attributes:

- title (optional): Connected document’s title

- url (required): Connected document’s url

- hash (optional): SHA256 hash of the connected document’s content.

- HDOC: Hash is calculated over

textContent, not the HTML orinnerText(to avoid whitespace modifications affecting highlight indices). - CDOC: Hash covers the entire

<svg>section, including the<svg>tag. - Currently, the hash is generated upon export but is not verified when loading documents. This feature will be added later.

- HDOC: Hash is calculated over

Child Elements of <doc>

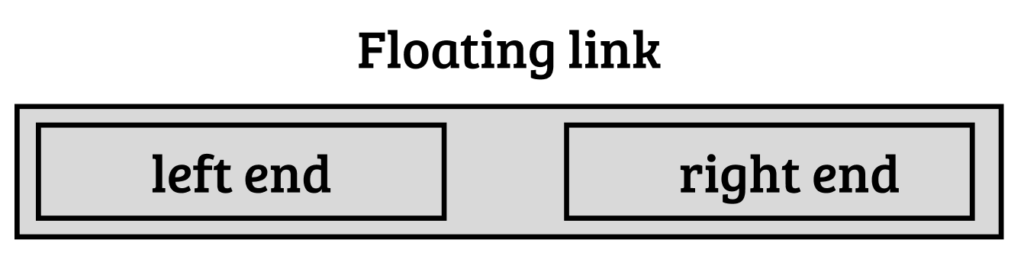

A <doc> may contain floating links, which link:

- Text segments in HDOCs

- Points in collages (CDOCs)

- Points in 3D scenes (SDOCs, not supported currently)

Floating links are presented as lines with key value pairs. Examples:

i:6771;l:22;h:abb7b7;e:MjE=_i:35;l:22

i:7494;l:34;h:7ac799;e:TzI=_i:59;l:28;h:3fa088

i:611629;l:149;h:f01591;e:VGw=_p|x:31.166;y:209.243;r:0.297

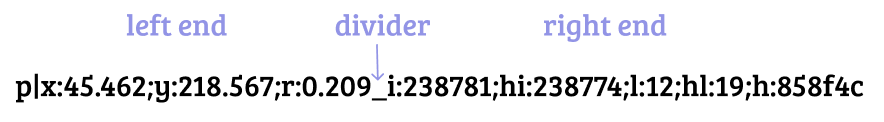

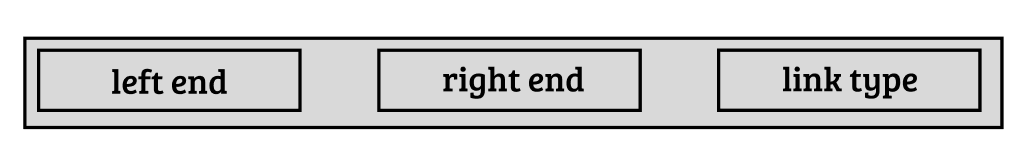

i:238781;hi:238774;l:12;hl:19;h:858f4c;e:dmE=_p|x:45.462;y:218.567;r:0.209A floating link has two ends:

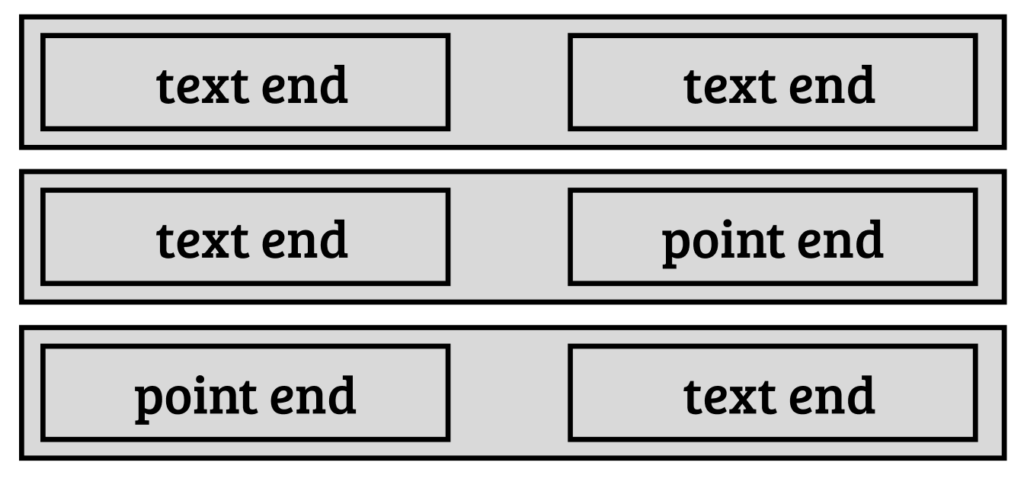

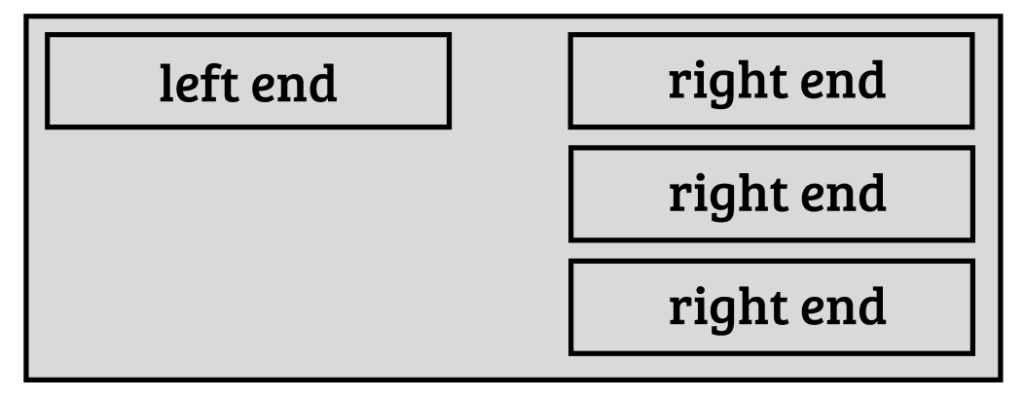

What end you use, depends on the document. For text documents you use a text end, for collages – a point end. There may be different combinations.

Point-to-point links, for visible connections between two collages, are currently not supported but may be supported in the future.

Two parts of a floating link are divided by an underscore.

Point end

Example:

p|x:45.462;y:218.567;r:0.209p→ Point end typex, y→ 2D coordinates in a collager→ Radius of a visible marker

Text end

Example:

t|i:47703;l:33;h:c85272;e:QTI=t→ Text end type (default, can be omitted)i→ Index of the first character of the highlighted textl→ Length of the highlighted texthi→ Index of hashed rangehl→ Length of hashed rangeh→ SHA256 hash- e → Ends of hashed range (first and last letter of hashed range concatinated into one string and then base64 encoded)

Most text ends will appear without the t prefix:

i:47703;l:33;h:c85272;e:QTI=Hashes in text ends

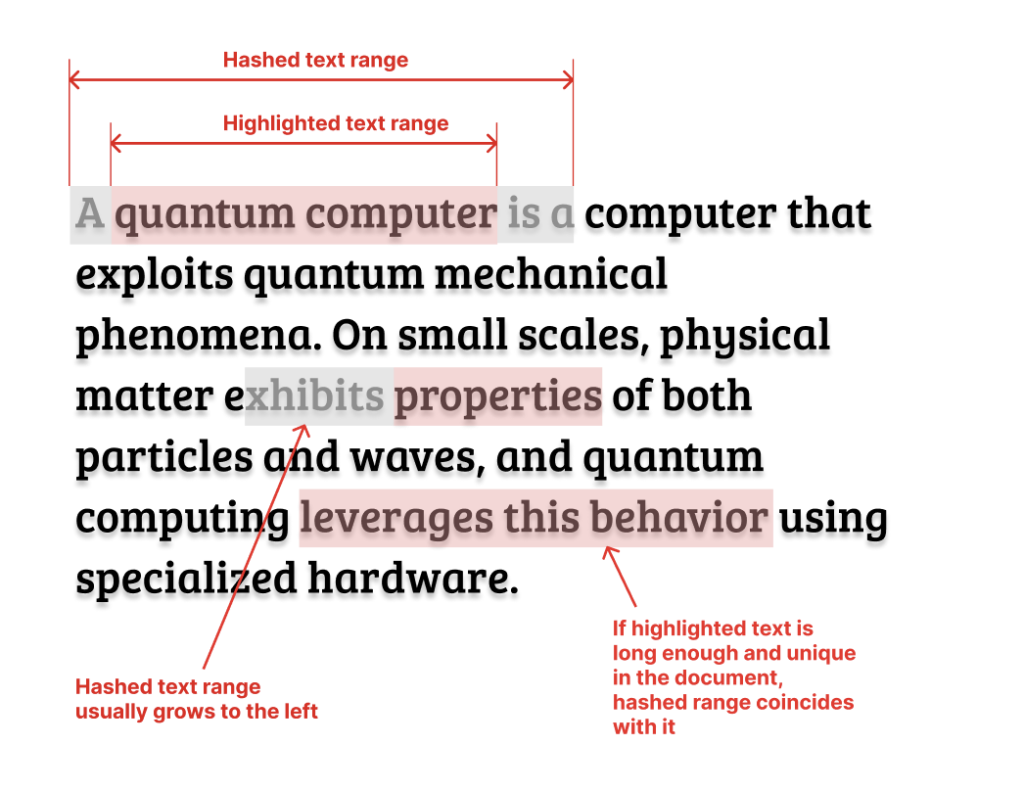

Hashes are used, so we could tell if the link is broken because the text of a document was changed. And if the link is broken, in many cases the hash can help fix it by moving it to another index. The client app can simply move a range of a known length across the text and check at each tested index if the hash of a text within that range matches the known hash.

- Hashes are generated for text segments that are unique and at least 10 characters long (character limit is used by LZ Desktop app when creating floating links, but it is not a requirement that will be set as a Web standard that all client apps must follow).

- If highlighted text is too short or non-unique, the hash is computed for a larger surrounding range.

- Default behavior: The hashed range extends left unless near the start of the document, in which case it can grow right as well.

When the highlighted text is both long enough and unique, the hashed range coincides with it, making hi and hl unnecessary:

i:6771;l:22;h:abb7b7;e:MjE=For text-to-text links, if both ends have the same hash, the second hash can be omitted. If the hashed range ends are the same (regardless of whether the hashes are the same or not) the “e” in the second text end can be omitted as well:

i:6771;l:22;h:abb7b7;e:MjE=_i:35;l:22Ends of hashed range are stored so that if the link is ever broken, it can be fixed in a reasonable time. If you only use hashes, you may have to test a large number of positions in text by calculating hash for each of them. If the web page is a size of a book, it can take, for example, 30 seconds or even a minute to fix all broken links.

If you know the first and last letter of the hashed string, you don’t need to check all possible positions, but only the ones where the first and the last letter match those stored in “e”. Because of that, the links with “e” parts can be fixed almost instantly.

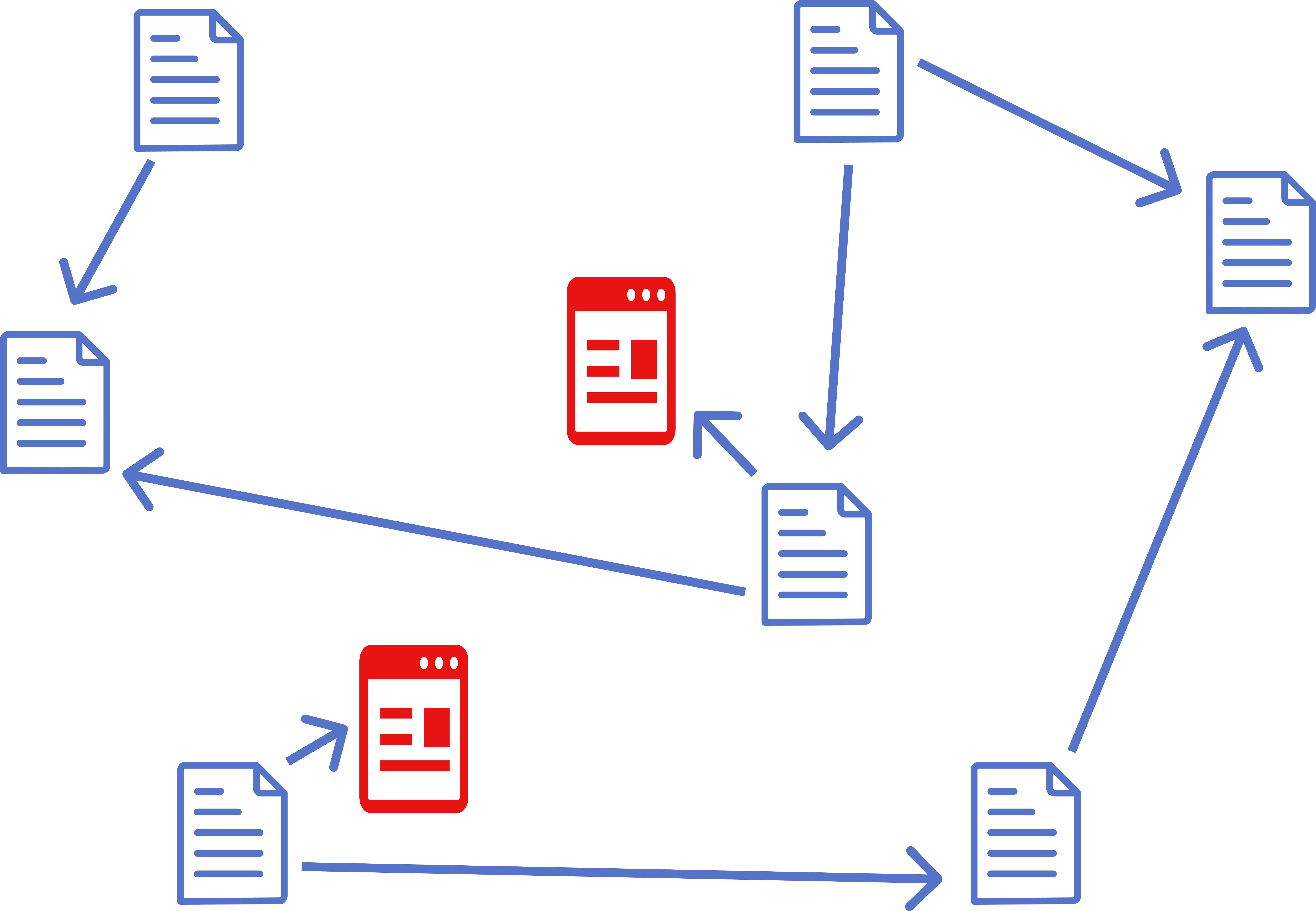

How this format can be extended

I have only implemented floating links for the simplest possible use cases. In the future a lot more options can be added.

We may want to be able to have multiple ends for one floating link. For example, you may want to create one commentary that is connected to multiple places in another document.

We may need to distinguish different types of links. So, a type field can be added to floating links.

Types can be, for example, Reference Link, Commentary Link, Correction Link, and many others. Some links may not even be links between two documents, but simply annotations within one document.

New floating link ends

For CDOCs (2D collages) a lot more link ends can be added besides a simple point marker. For example, you may want to frame something with a rectangle. You may want to add texts as overlays. All such cases can be handled by introducing new floating link ends.

A collage may contain texts, so maybe we should be able to have text ends that are used in collages.

Also, it may be useful to be able to target specific images within a collage instead of using absolute coordinates. This way, if an image position was changed, the link will not be broken.

In 3D scenes (SDOCs) a support for 3D point ends and possibly other types of ends may be added in the future.

Proper Xanalinks

As I mentioned in other posts, this project is inspired by Ted Nelson’s project Xanadu. In Xanadu, there was a completely different mechanism for stabilising content of documents, so that links are never broken. That mechanism can be used in the Web 1.1 as well. It probably won’t be widespread, but I think it should exist as an option.

Documents that support that mechanism, will be simply HDOCs that have an <edl> section.

A new floating link end will be introduced for Xanalinks. It will be more complex than a regular text end with a hash.

Because it’s just one end, it can be combined with other types of ends. So, you’ll be able to connect a Xanadoc (HDOC with an EDL section) to a regular HDOC. Or to a collage, 3D scene, or another Xanadoc.

If for whatever reason you don’t want to use stabilized content addresses from EDL you’ll be able to use a simple text end over a Xanadoc. But in this case you won’t be using all the features a Xanadoc can provide.

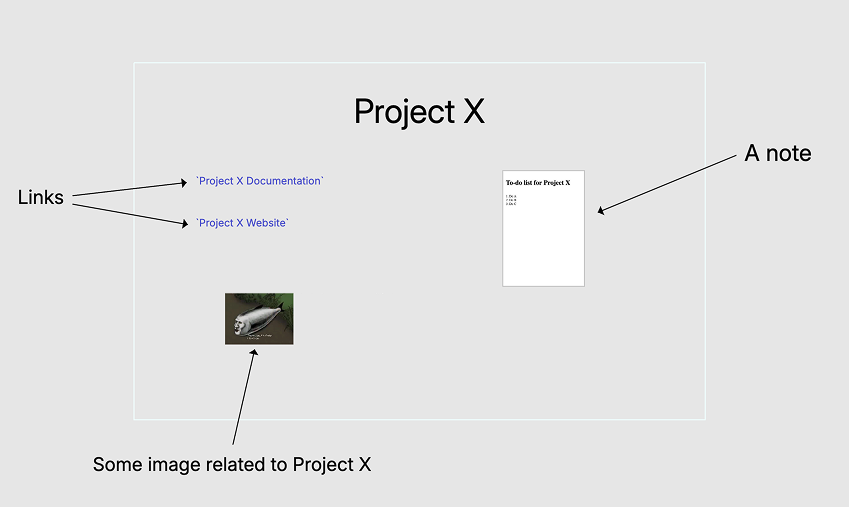

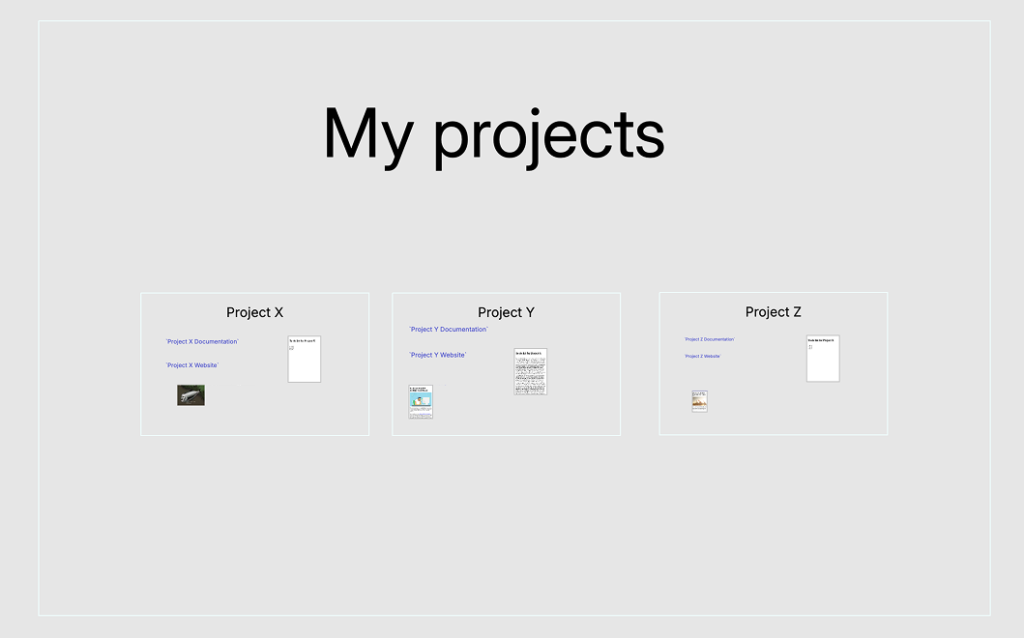

An example of an HDOC with CONNECTIONS section:

<hdoc>

<content>

Content of the document...

</content>

<connections>

<doc url="https://example.com/dates" title="Dates" hash="d79712">

i:6771;l:22;h:abb7b7;e:MjE=_i:35;l:22

i:7494;l:34;h:7ac799;e:TzI=_i:59;l:28;h:3fa088

i:47703;l:33;h:c85272;e:QTI=_i:116;l:27;h:8de52f

</doc>

<doc url="https://example.com/collage" title="Collage" hash="54dfa4">

i:611629;l:149;h:f01591;e:VGw=_p|x:31.166;y:209.243;r:0.297

i:238781;hi:238774;l:12;hl:19;h:858f4c;e:dmE=_p|x:45.462;y:218.567;r:0.209

</doc>

</connections>

</hdoc>