The way I have presented Web 1.1 so far might make it seem like it’s all about saving documents locally in spatial environments. But that’s not the whole picture.

The new proposed data types – HDOC, CDOC, and SDOC – can be used anywhere. Specifically, they can function within a regular browser, inside tabs. These data types are just special types of web pages.

If all goes well, I plan to develop the first Web 1.1-compatible browser this year. However, this is only a small step and not an urgent one, since there isn’t yet enough Web 1.1 content to necessitate a dedicated browser.

For now, we can use Web 2 for navigation and discovery, and Web 1.1 will be used for saving. But that’s a temporary arrangement.

The Big Goal

Ultimately, the aim is to encourage mainstream browsers to support Web 1.1 data types. The way to achieve this is by making Web 1.1 widespread on existing websites first.

Initially, Web 1.1 will require a special app like LZ Desktop for saving documents in spatial environments. Not many people will use such apps, as many don’t even own personal computers. But that’s not a problem. Websites may still support Web 1.1 to accommodate those few who want to use Static Web.

I’ve discussed incentives for website owners to support Web 1.1 in another post.

What to expect in the future

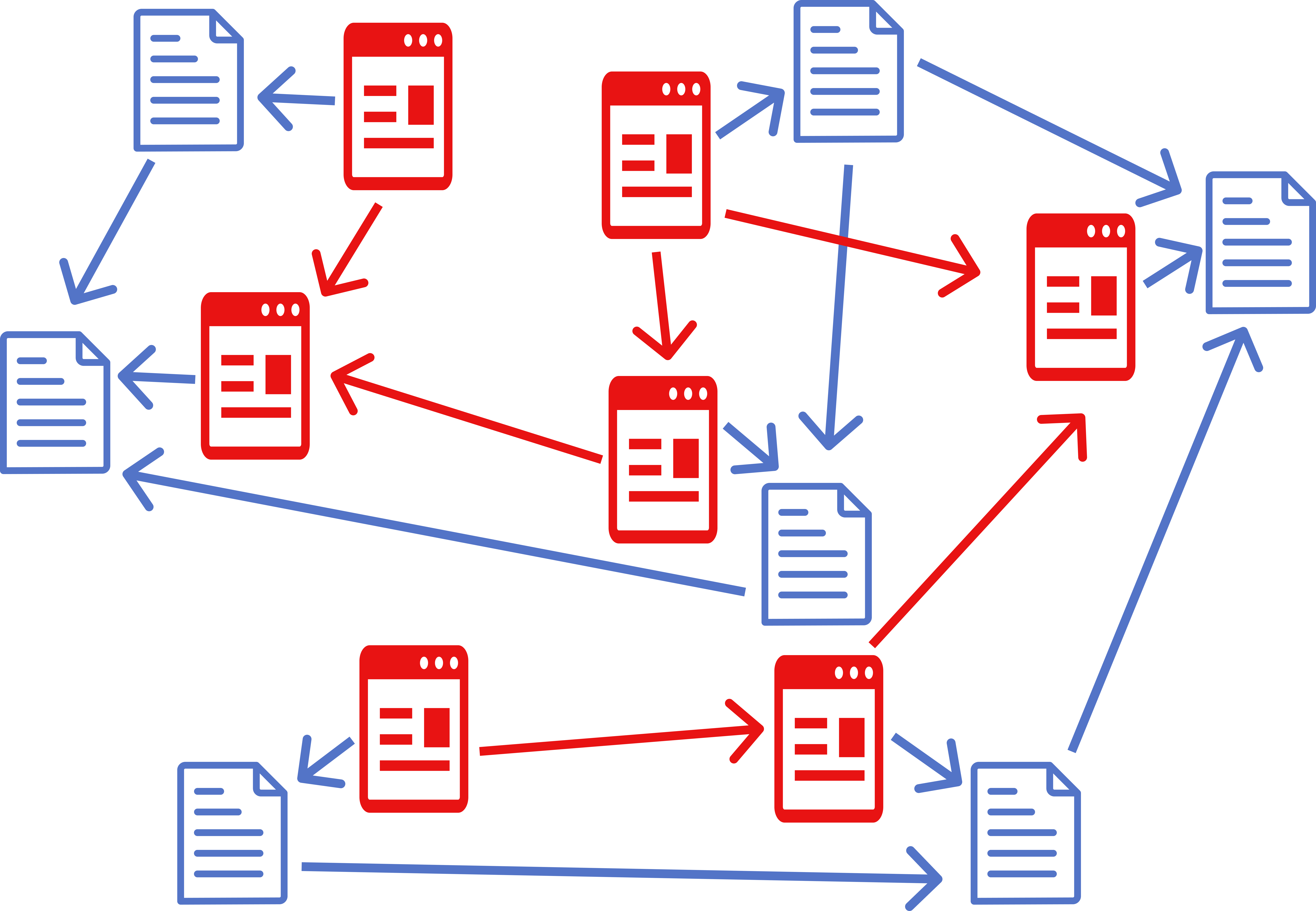

As more websites adopt Web 1.1, mainstream browsers will have more reasons to support its data formats—just as they currently support viewing PDFs. Eventually, they could support HDOCs, CDOCs, and SDOCs, even displaying visible connections between them.

Once Web 1.1 documents can be used in regular browsers, search engines may start indexing them, just as they do with HTML pages and PDFs.

A New Type of Website

With browser and search engine support, Web 1.1 documents will become first-class citizens of the web. You’ll be able to build an entire website using only these new data types, without any traditional HTML pages.

Technically, you could do this right now, but it wouldn’t be practical without browser and search engine support—most users wouldn’t be able to find or view your content.

The Three Stages of Web’s Evolution

I like to compare this transformation to the lifecycle of a butterfly. Why? Because just as a butterfly looks nothing like its initial form—a caterpillar—the Static Web, in its final form, will be vastly different from what it is today. So, the three stages of the web’s evolution can be named:

- Caterpillar

- Pupa

- Butterfly

Caterpillar Stage (Current Phase)

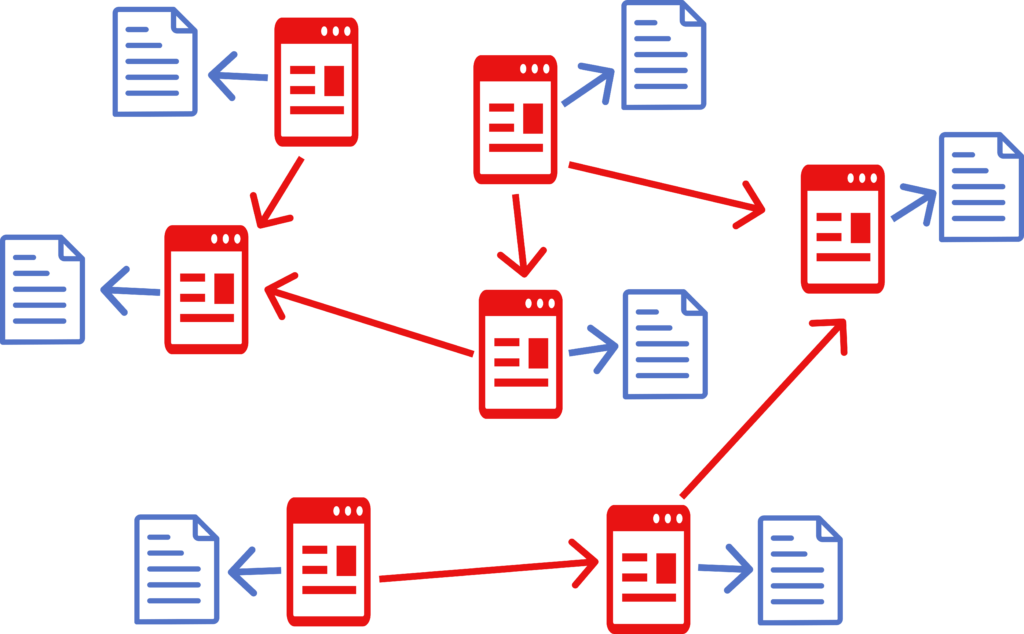

At this stage, Web 1.1 is used only for saving content. Navigation and discovery still rely on Web 2 pages and traditional browsers.

Pupa Stage

This stage begins when mainstream browsers start supporting Web 1.1 data types. Users will then be able to navigate both Web 1.1 and Web 2 within their browsers. However, website owners will still need to maintain Web 2 versions, as many users will continue using browsers that don’t yet support Web 1.1.

Butterfly Stage

This final stage begins when all major browsers and search engines fully support Web 1.1. On this stage you can remove Web 2 pages from your website and replace them with redirects to Web 1.1 versions of the same pages. Web 2 will shrink.

Timeline for Transformation

I don’t know how long this transition will take. It could fail early on if Web 1.1 doesn’t gain momentum. But since there’s no limit on retries, we can keep pushing forward.

If we manage to get a critical mass of websites to support Web 1.1, I think, we can duplicate entire Web rather quickly, because users and website owners are incentivised to use Static Web, and there will be an element of social proof at play, because you will see download buttons all over the Web.

Then we may get stuck on the Pupa stage. If a major browser or search engine refuses to support Web 1.1 formats, the transition could stall. However, if enough of the web shifts to Web 1.1, they will have to adopt it eventually.

Overall, this transformation will take years—possibly many years. But Web 1.1 offers immediate benefits at every stage, even in its early form.

This isn’t some far-off vision that depends on universal adoption. A small group of enthusiasts can start by publishing their websites on Static Web. Other website owners will follow because it enhances user engagement and retention. Eventually, this process may transform the entire web.

What Web 1.1 Might Look Like in the Future

I see two major developments on the horizon for Web 1.1:

- Web 1.1 as a Decentralized Social Network

- Xanadufication of the Web

I will briefly describe them here, but I will discuss them in more detail in other posts.

Web 1.1 as a Decentralized Social Network

Several projects, such as Bluesky’s AT Protocol and Tim Berners-Lee’s Solid project, aim to decentralize the web. They give users control over their data, hosting it on personal servers while allowing apps to access it.

However, these projects face adoption challenges because they require individuals to host their own content—something most people won’t do.

Web 1.1 can present an alternative solution to the same problems those projects aim to solve. In Web 1.1 the pages (HDOCs) are much more standardised than regular HTML pages. They have only one column of text and standard navigation panels. It reminds me of social networks where you just provide your content and don’t have a say in how the website looks.

To make Web 1.1 a social network we need only to standardize a few things.

For instance, every Web 1.1 site could include a standardized News page for posting short updates (like tweets). A standard “Follow” button would allow users to subscribe to these updates. Aggregator services could scrape these updates and generate personalized feeds—similar to Twitter’s “For You” section.

Unlike other decentralization efforts, Web 1.1 targets website owners who already host content. They only need to install a plugin to participate, making adoption much easier.

More than that, those people have other incentives to support Web 1.1 beyond simply participating in a social network.

I plan to study AT Protocol and Solid project to understand if our approaches can be merged or at least aligned somehow. One possibility I see for them is to start providing a CMS (Content management system) that allows your to create a website made of HDOCs. But that will be practical only on Butterfly stage. If you do it now, you’ll have to support Web 2 as well, and that may be too complicated.

Xanadufication of the Web

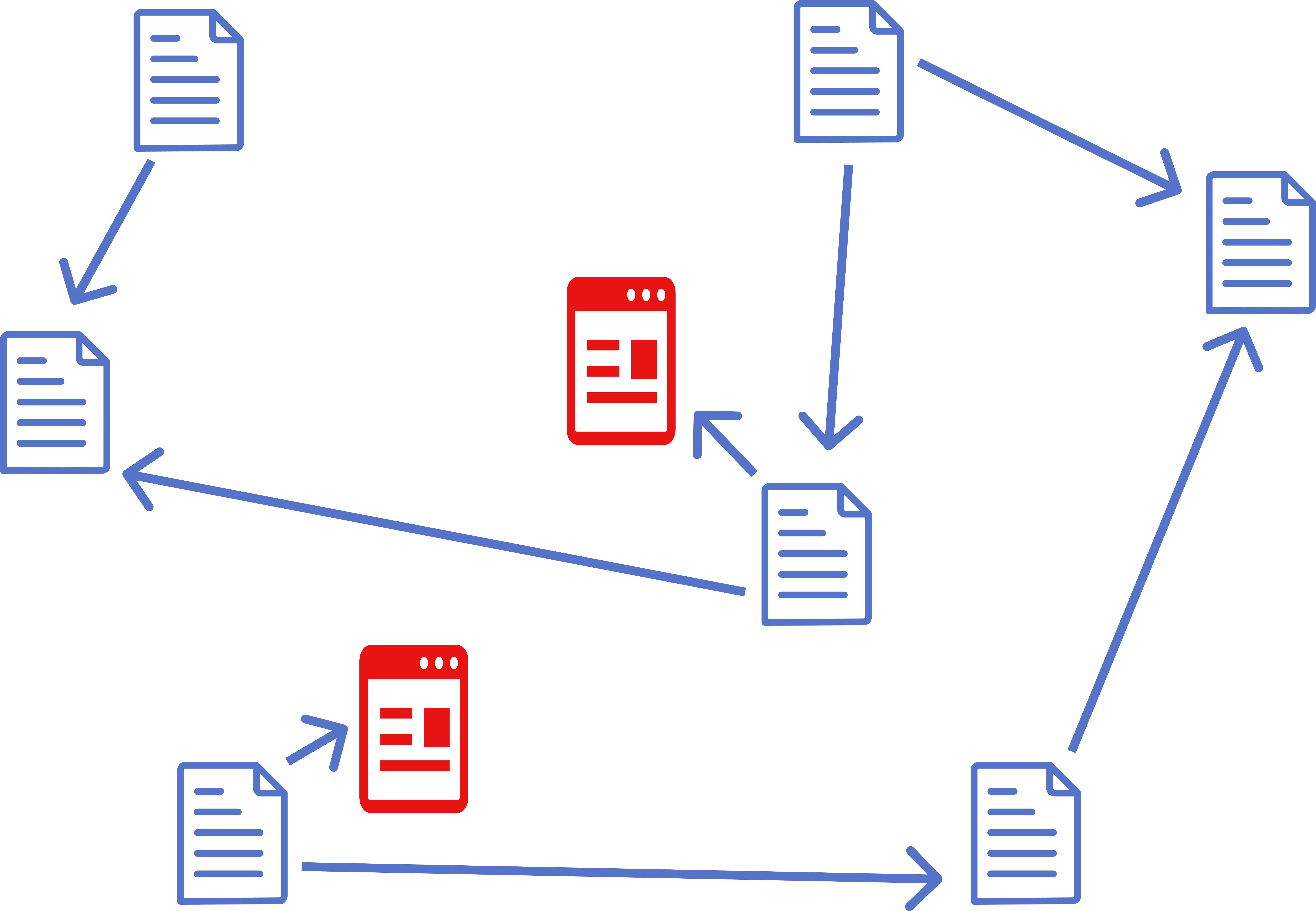

Web 1.1 is heavily inspired by Ted Nelson’s Xanadu project, which introduced concepts like visible connections between texts, transclusions, and versioning.

In Web 1.1 we have visible connections between texts. But those are simplified links. They are not as powerful as proper xanalinks. But there is a way to add more Xanadu-like features to the Web. I have a more or less detailed plan of how it can be done.

I will dive deeper into details in another post, but here I will just mention key differences between my proposed implementation and that of the original Xanadu project. Here I assume that you have a detailed knowledge of Xanadu project. If you don’t, I’ll explain everything in another post.

Here are the main differences:

- Most documents will not be assembled on the client, only on the server. Exceptions will be made when a paid content, that comes from some publishing platform, is involved.

- EDL will not be a separate document, instead it will be included into an HDOC.

- Layout (headers, paragraphs, etc.) will be done using HTML. ODL may be stored on the server, but overlays will apply HTML tags to texts. So, there will be, for example, H1 overlay, P overlay, A overlay, and so on. ODL will not be included in HDOC, because all the necessary information will already be in the HTML.

- Many servers will not store texts separately from EDLs. They will pretend to do so. Texts in HDOCs will have stabilized addresses as if they are stored in some files somewhere but in many cases they will be only stored in their HDOCs.

- Websites will decide whether to adopt Xanadu-style features. Client apps will distinguish between simple HDOCs and HDOCs with an EDL section. Both simple links and proper xanalinks will be supported by client apps.

A lot of smaller websites will either not use additional features at all, or use them in a very limited way. In a decentralized setting features like transclusions and selling pieces of content may be too impractical.

But if somebody creates a big publishing platform where people can publish and sell their content, they can design it very close to the original specifications of the Xanadu project and plug it into the Web 1.1 ecosystem that will support the new advanced features.

In short, you will have transclusions and micro-transactions, and versioning on big websites. But it will be possible to create visible connections from those big websites to the content from other smaller websites that don’t have those features.

A lot of Xanadu’s features require a degree of centralization. So, it only makes sense that you won’t find them everywhere on the Web, but only on some larger websites.

Conclusion

There are 3 stages of Web’s transformation. Besides that, there are two possible developments in the future: Web turning into a decentralized social network and Xanadufication of Web.

I will focus on these two developments only when it becomes clear that Web 1.1, in its simplest form, is gaining traction.

More details to come in future posts.